In the case of Big Telecommunications, buying politicians pays off handsomely by killing the competition.

By Matt Stoller, Republic Report

Posted on April 11, 2012

Last year, a new company called Lightsquared promised an innovative business model that would dramatically lower cell phone costs and improve the quality of service, threatening the incumbent phone operators like AT&T and Verizon. Lightsquared used a new technology involving satellites and spectrum, and was a textbook example of how markets can benefit the public through competition. The phone industry swung into motion, not by offering better products and services, but by going to Washington to ensure that its new competitor could be killed by its political friends. And sure enough, through three Congressmen that AT&T and Verizon had funded (Fred Upton (R-MI), Greg Walden (R-OR), and Cliff Stearns (R-FL)), Congress began demanding an investigation into this new company. Pretty soon, the Federal Communications Commission got into the game, revoking a critical waiver that had allowed it to proceed with its business plan.

And so Americans continue to have a small number of expensive, poor quality cell phone providers. And how much does this cost you? Take your phone bill, and cut it by 80%. That’s how much you should be paying. You see, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, people in Sweden, the Netherlands, and Finland pay on average less than $130 a year for cell phone service.

Americans pay $635.85 a year. That $500 a year difference, from most consumers with a cell phone, goes straight to AT&T and Verizon (and to a much lesser extent Sprint and T-Mobile). It’s the cost of corruption. It’s also, from the perspective of these companies, the return on their campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures. Every penny they spend in DC and in state capitols ensures that you pay high bills, to them.

This isn’t obvious, because much of how they do this has to do with the structure of the industry.

This has implications for your cell phone bill. Once AT&T or Verizon has paid for its network and licensed spectrum from the government, the cost of adding an additional customer is very low. That means that the biggest providers with bigger networks and more licensed spectrum make more money. It’s not only that their costs are lower, but also because they can keep other players out through control of the political system. That is, they can move towards monopoly in the industry. And monopoly means higher prices for you, and more profits for them. Here’s the data.

Verizon and AT&T’s Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) are substantially higher than any other national carrier’s. Verizon’s wireless profit margins (EBITDA) are substantially higher than all other carriers except AT&T. And Verizon and AT&T together control four-fifths of the entire wireless industry profits, the only two major carriers to control double-digit shares of the industry’s total profits. Over the past 3 years Verizon and AT&T’s share of total industry profits has steadily increased while everyone else’s declined.

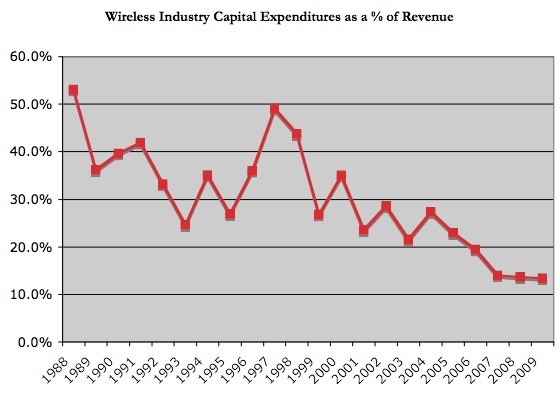

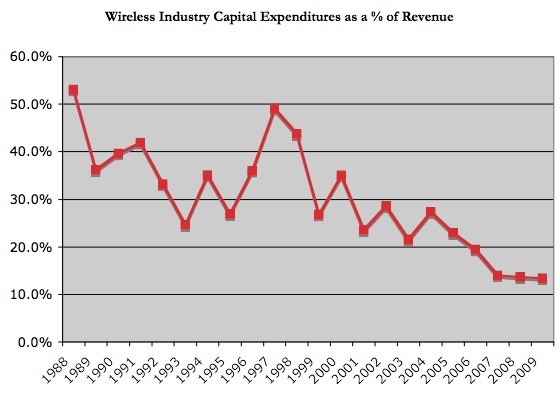

This of course doesn’t mean that these companies are investing more in their networks, for better service for you and me. In case you haven’t noticed, cell phone coverage is still really bad, and calls drop routinely. The chart below can explain why. The data is from the CTIA, or the Wireless Association, and it shows the effect of industry consolidation.

Basically, what this chart shows is that in the 1990s, cell phone companies bought up other cell phone companies, and Congress and the FCC were happy to go along because of the power of industry lobbying. Once these companies had an effective cartel, their amount of investment dropped. If you didn’t like your cell phone company, you couldn’t really switch, because the other big cell phone company was just as bad. In 1997, the industry was putting 50 cents of every dollar of revenue into investing in more cell phone towers. By 2009, that number dropped 12.5 cents of every dollar. CTIA has made it much harder to find this data since 2004, but it is obscure filing comments at the FCC. Pretty soon, we should expect the public not to even be able to track why our cell phone’s usage is so bad.

To reduce prices in such a system, you need either competition in the form of more networks (with the same or different technology) or price regulation. The Federal Communications Commission has neither forced more competition, nor has it restricted price gouging. In fact, by doing things like killing Lightsquared, it has ensured high prices for all of us. Furthermore, the FCC has allowed a small number of big players like AT&T and Verizon to buy up much of the public airwaves (or “spectrum”) available for cell phone use, just to keep out competitors. It tends to allow big mega-mergers to go through (with the exception of the recent T-Mobile and AT&T merger). Meanwhile, Congress is trying to tie the hands of the FCC on making more spectrum available for anyone to use, and broadcasters are also throwing their lobbying into the ring, because they want to be able to control more spectrum to transmit television signals.

Why does the FCC and why does Congress want us to have high cell phone costs? Well, they don’t, not really. It’s more accurate to say they don’t particularly care about our problems, but are responding to an entirely different problem that is completely unrelated to cell phones. The government is responding to the need for campaign contributions for politicians.

Politicians need huge sums of money to run for office. Just a regular Congressman (and remember, there are 435 of these) needs $2 million on average to win reelection – which is about $20,000 per week he’s in office. He needs this money to buy TV ads. Unlike in other countries, where political parties get free TV time or public money to pay for elections, American politicians get this money from private interests. Some of the biggest donors, in fact the single biggest donor, is AT&T, with Verizon in the top 100. These politicians lobby regulatory agencies like the Federal Communications Commission to make sure these companies can do what they want, and politicians make sure that phone companies get to buy up other phone companies, eventually creating a near monopoly situation. And we all know that monopolies charge more and deliver less to their customers. As telecom legal expert Marvin Ammori said, “It’s proven cheaper to buy politicians than invest in high speed broadband or to provide good customer service at a fair price. ”

In other words, we are stuck with big bad cell phone companies not because those companies are good at providing cell phone service (which anyone with a dropped cell phone call knows), but because they are good at corrupting markets through political donations. AT&T has the single biggest donor group (known as a “Political Action Committee”) in Washington, DC.

Again, that’s on average $500 a year, $40 a month, or $1.50 a day, from you, straight into the pockets of Verizon and AT&T.

This isn’t obvious, because much of how they do this has to do with the structure of the industry.

Telecommunications isn’t like selling apples, where you have a lot of buyers and sellers. In a business like buying or selling apples, all you need is an apple tree to get into the business. Cell phones aren’t like that. It’s a business where you sell services on top of a network of cell phone towers that can transmit phone calls and data, and these networks cost tens of billions of dollars to build. But even if you have the money to build one, you still might not be able to, as the Lightsquared example shows. These networks all use public airwaves, or “spectrum”, and you need government permission to use it. Remember the electromagnetic spectrum you learned about in school? The government literally leases that out to companies, and they make radios, microphones, wifi routers, and cell phones that use it.

This has implications for your cell phone bill. Once AT&T or Verizon has paid for its network and licensed spectrum from the government, the cost of adding an additional customer is very low. That means that the biggest providers with bigger networks and more licensed spectrum make more money. It’s not only that their costs are lower, but also because they can keep other players out through control of the political system. That is, they can move towards monopoly in the industry. And monopoly means higher prices for you, and more profits for them. Here’s the data.

Verizon and AT&T’s Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) are substantially higher than any other national carrier’s. Verizon’s wireless profit margins (EBITDA) are substantially higher than all other carriers except AT&T. And Verizon and AT&T together control four-fifths of the entire wireless industry profits, the only two major carriers to control double-digit shares of the industry’s total profits. Over the past 3 years Verizon and AT&T’s share of total industry profits has steadily increased while everyone else’s declined.

This of course doesn’t mean that these companies are investing more in their networks, for better service for you and me. In case you haven’t noticed, cell phone coverage is still really bad, and calls drop routinely. The chart below can explain why. The data is from the CTIA, or the Wireless Association, and it shows the effect of industry consolidation.

Basically, what this chart shows is that in the 1990s, cell phone companies bought up other cell phone companies, and Congress and the FCC were happy to go along because of the power of industry lobbying. Once these companies had an effective cartel, their amount of investment dropped. If you didn’t like your cell phone company, you couldn’t really switch, because the other big cell phone company was just as bad. In 1997, the industry was putting 50 cents of every dollar of revenue into investing in more cell phone towers. By 2009, that number dropped 12.5 cents of every dollar. CTIA has made it much harder to find this data since 2004, but it is obscure filing comments at the FCC. Pretty soon, we should expect the public not to even be able to track why our cell phone’s usage is so bad.

To reduce prices in such a system, you need either competition in the form of more networks (with the same or different technology) or price regulation. The Federal Communications Commission has neither forced more competition, nor has it restricted price gouging. In fact, by doing things like killing Lightsquared, it has ensured high prices for all of us. Furthermore, the FCC has allowed a small number of big players like AT&T and Verizon to buy up much of the public airwaves (or “spectrum”) available for cell phone use, just to keep out competitors. It tends to allow big mega-mergers to go through (with the exception of the recent T-Mobile and AT&T merger). Meanwhile, Congress is trying to tie the hands of the FCC on making more spectrum available for anyone to use, and broadcasters are also throwing their lobbying into the ring, because they want to be able to control more spectrum to transmit television signals.

Why does the FCC and why does Congress want us to have high cell phone costs? Well, they don’t, not really. It’s more accurate to say they don’t particularly care about our problems, but are responding to an entirely different problem that is completely unrelated to cell phones. The government is responding to the need for campaign contributions for politicians.

Politicians need huge sums of money to run for office. Just a regular Congressman (and remember, there are 435 of these) needs $2 million on average to win reelection – which is about $20,000 per week he’s in office. He needs this money to buy TV ads. Unlike in other countries, where political parties get free TV time or public money to pay for elections, American politicians get this money from private interests. Some of the biggest donors, in fact the single biggest donor, is AT&T, with Verizon in the top 100. These politicians lobby regulatory agencies like the Federal Communications Commission to make sure these companies can do what they want, and politicians make sure that phone companies get to buy up other phone companies, eventually creating a near monopoly situation. And we all know that monopolies charge more and deliver less to their customers. As telecom legal expert Marvin Ammori said, “It’s proven cheaper to buy politicians than invest in high speed broadband or to provide good customer service at a fair price. ”

In other words, we are stuck with big bad cell phone companies not because those companies are good at providing cell phone service (which anyone with a dropped cell phone call knows), but because they are good at corrupting markets through political donations. AT&T has the single biggest donor group (known as a “Political Action Committee”) in Washington, DC.

Again, that’s on average $500 a year, $40 a month, or $1.50 a day, from you, straight into the pockets of Verizon and AT&T.

No comments:

Post a Comment