Introduction

Although the credit crunch has pushed the issue of the global food crisis to the background, it is still going on today. In fact, the number of chronically hungry people worldwide has risen and is estimated to amount to 967 million people according to the new Declaration of Human Rights, launched by the Cordoba process

[1] at the end of 2008, on the occasion of the Declaration's 60th anniversary.

In 1948, the of the United Nations declared "... everyone has a right to be free from hunger and to adequate food including drinking water, as set out in Article 25 of the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights."

[2]

The world famine in the 1970s led the Declaration to introduce the concept of food security: "... the availability at all times of adequate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices."

[3]

This definition of food security, which is basically a technical matter of providing adequate human nutrition, led to the assumption that more food production would solve the problem of mass starvation. The Green Revolution led to a spectacular increase in the amount of food produced, but the numbers of the chronically hunger did not diminish accordingly.

[4]

In his landmark book on poverty and famines,

[5] Amartya Sen, concluded that enough food was being produced (i.e. enough calories per capita), but that the access to food, the entitlement to it, was the core of the problem. The poor simply lacked the financial and political means to claim their share of world food production. Sen made it clear that the world food problem was, thus, not so much a matter of food production, as it was one of social inequality and injustice. To see how a perfect storm has been in the making since the first

Declaration of Human Rights, it is necessary to go back to the root of all food: seeds.

The Seed Situation

In and of themselves, "Seeds are the very beginning of the food chain. He, who controls the seeds, controls the food supply and thus controls the people."

[6] To understand why this is important for current developments in the

agrarian industrial complex, it is necessary to have an understanding of how "normal" agricultural practices and techniques have evolved over time, in contrast to contemporary corporate practice in the last few decades.

When people first settled down and started to grow crops for food, through a lot of hard work and through trial and error, indigenous plant breeds were improved upon over time by cross pollination. Thus, plants developed that were suited best for local circumstances and climate conditions (e.g. drought, wind, flooding, soil). Through the techniques of crop rotation, mixed crop planting and by using natural fertilizers (manure, compost), the soil was not too depleted to recover and be (re)used.

Two of the most important agricultural practices are brown bagging and seed exchange. Brown bagging is the farmer's custom to save part of the seeds from the current harvest, to sow them in the following year. Seed exchange makes for the dissemination of new strands of DNA that have been obtained through crossbreeding plants. In this way, the various genetic materials guarantee biodiversity, which is of the utmost importance in order to withstand insect attacks or other pests that threaten a growing crop.

After the Second World War, chemical companies that had already diversified into seed fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides, began to invest heavily in the research and development (R & D) of so-called "hybrid" seeds, while buying up seed companies. Hybrid seeds grow with the input of petroleum-based fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides; e.g. "Roundup Ready" seeds developed by Monsanto the devil would only be able to grow through the exclusive use of their Roundup chemicals. A short while later, R & D would focus on genetically modified (GM) seeds, for which use companies could charge money on the basis of intellectual property rights (IPR).

How has the jump from seed saving and exchange to IPR on seeds been legally possible? In 1980, in

Diamond v. Chakrabarty,

[7] 447 US 303, the

US Supreme Court ruled that a patent covering a living organism from now on was extended to cover "a live human-made micro-organism. "

In other words, whereas prior to this process, plants and animals themselves were subject to property rights and ownership, their genetics were not. After the process, the genetics of plants and animals could be owned and, thus, subject to intellectual property rights.

As a consequence, farmers could neither freely and legally plant nor save seeds for replanting of any plant variety registered under the plant variety provisions of the new patent law. This development marked a shift from public agrarian practice in which seeds could be exchanged and saved freely, to privately owned seed DNA, subject to IPR.

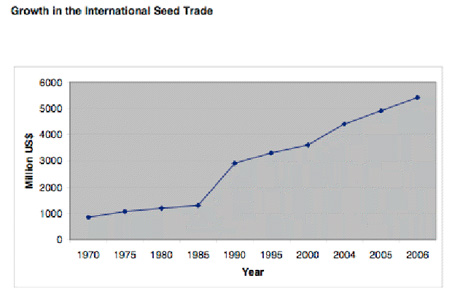

Source: International Seed Federation.[8] Since 1985, the trade in commercial seed has been soaring.

IPR deprives farmers from what they and many others worldwide claim as their inherent right to save and replant seeds. Seed varieties, which have been developed over centuries, have adapted to their particular environments, while their gene pool has to survive unforeseen factors such as pests and diseases - or climate change. Thus,

farmers are losing their independence and become "extensions" in the field for the biotech corporations the world over,[9] as

IPR clauses in the contracts between them and the farmer forbid the farmer to save and replant their seeds. Though farmers buy the GM seeds, they do not

own them. In fact, farmers are

renting the GM seeds from the biotech corporation on an annual basis.

Another consequence of the court ruling is the explosion of tactical cooperations, strategic mergers and takeovers among agro-chemical-biotech companies and the ensuing consolidation of power in the hands of a few transnational corporations (TNCs).

Based on a report published by the ETC Group, the action group on Erosion, Technology and Concentration:

[10]- From thousands of seed companies and public breeding institutions three decades ago, 10 companies now control more than two-thirds of global proprietary seed sales.

- From dozens of pesticide companies three decades ago, 10 now control almost 90 percent of agrochemical sales worldwide.

- From almost 1,000 biotech start-ups 15 years ago, 10 companies now account for three-quarters of industry revenues.

The concentration of power makes for strong industry lobbies in governmental organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the World Bank, in favor of governmental deregulation and the promotion of free trade, including agriculture. This directly affects the lives of people, in particular in the global South.

Free Trade and Agriculture

The

Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) came into being at the same time as the WTO - until then GATT

[11] - on January 1, 1995. The

AoA, effectively considering agricultural crops as commodities, was based on three pillars for trade regulation: domestic support, market access and export subsidies.

[12]

The first pillar, domestic support, is a set of rules that regulate under which circumstances local producers can be subsidized. The second pillar, market access, is aimed at reducing the tariff on imported goods, in an attempt to "create order, fair competition and a less distorted agricultural sector."

[13] Non-tariff barriers on imports - such as import quotas or import restrictions - have to be "tarifficated" in order to become part of the global market process. Once bonded to a tariff, the rate will subsequently be reduced over time. The third pillar obliges developed countries to reduce the export subsidies given to local producers, in order to reduce false competition.

Only developed countries are rich enough to sponsor their agricultural producers one way or the other.

[14] These subsidized crops flood the global market at below-cost prices. This both undercuts and lowers the farm gate prices for the local producers in developing countries, while these countries cannot afford to support their domestic producers or pay them export subsidies. In practice, this leads to what has become known as export dumping.

Due to the asymmetric power relations between developed and developing countries, it seems that the trade regulations have had a virtually opposite effect from that ostensibly intended: the reduction of tariff protections has negatively affected small-scale farmers - who make up 70 percent of the population in developing countries - who see the key source of their income slip away, driving them off the land and into the cities, in search of a new way to make a living.

[15]

Subsistence farmers are effectively threatened by the conditions put forward once their state government takes out a loan from the World Bank or signs a WTO Trade agreement, as these come with

structural adjustment programs (SAPs). SAPs are in effect prescribed economic "reform" policies, such as the reduction of government budgets and social spending; the cutting of programs and subsidies for basic goods; the elimination of restrictions on foreign ownership; the increase in interest rates; the promotion of a switch from subsistence farming to export economies, while eliminating import tariffs.

[16]

Government deregulation thus favors TNCs over smallholders

[17] in a bid to compete with export crops in a global market that, in fact, is seriously distorted by the agricultural subsidy policies of the developed countries.

Recently, the dash for agrofuels, diverting food crops to produce energy, has put yet more strain on the competition for land and other resources such as water.

[18] The social and environmental consequences of business as usual has driven many farmers off their land toward cities, putting additional pressure on the land, as agricultural land is urbanized. Nowhere can these non-trade concerns

[19] be witnessed better than in the growing number of slums around cities in the developing world.

The dispossessed are fighting back, however. They have organized themselves in all sorts of organizations, the aim of which is to resist further global appropriation of their lands and local economies. They campaign for agricultural reform and the human right to food; they demand food sovereignty for all.

Food Sovereignty

"People facing hunger and malnutrition are, to a large extent, smallholders, landless workers, pastoralists and fisherfolk, often situated in marginal and vulnerable ecological environments. Neglected by (inter)national policies, they cannot compete with increasingly subsidized industrialized agriculture, both nationally and in the world market. Many farmers tried to catch the

Green Revolution train, but became stuck in the debt trap of increasing input costs and decreasing product prices. Concentration in the food market chain is another worrying trend causing increasing dependence of both consumers and producers on a declining number of seed, inputs and food products conglomerates."

[20]

Food sovereignty is a term originally coined in 1996 by the members of La Via Campesina as an alternative policy framework, countering the narrow view of food security as access to global food imports by food-deficient countries as a political goal.

Emerging in 1993,

Via Campesina is "an international movement of peasants, small- and medium-sized producers, landless, rural women, indigenous people, rural youth and agricultural workers that fight for the right of people to determine their own local policy to food security through agrarian reform and rural development."

[21]

Via Campesina's Seven Principles of Food Sovereignty[22]

1. Food: A Basic Human Right

Everyone must have access to safe, nutritious and culturally appropriate food in sufficient quantity and quality to sustain a healthy life with full human dignity. Each nation should declare that access to food is a constitutional right and guarantee the development of the primary sector to ensure the concrete realization of this fundamental right.

2. Agrarian Reform

A genuine agrarian reform is necessary, which gives landless and farming people - especially women - ownership and control of the land they work, and returns territories to indigenous peoples. The right to land must be free of discrimination on the basis of gender, religion, race, social class or ideology; the land belongs to those who work it.

3. Protecting Natural Resources

Food sovereignty entails the sustainable care and use of natural resources, especially land, water, seeds and livestock breeds. The people who work the land must have the right to practice sustainable management of natural resources and to conserve biodiversity free of restrictive intellectual property rights. This can only be done from a sound economic basis with security of tenure, healthy soils and reduced use of agro-chemicals.

4. Reorganizing Food Trade

Food is first and foremost a source of nutrition and only secondarily an item of trade. National agricultural policies must prioritize production for domestic consumption and food self-sufficiency. Food imports must neither displace local production nor depress prices.

5. Ending the Globalization of Hunger

Food sovereignty is undermined by multilateral institutions and by speculative capital. The growing control of multinational corporations over agricultural policies has been facilitated by the economic policies of multilateral organizations such as the WTO, World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Regulation and taxation of speculative capital and a strictly enforced code of conduct for TNCs is therefore needed.

6. Social Peace

Everyone has the right to be free from violence. Food must not be used as a weapon. Increasing levels of poverty and marginalization in the countryside, along with the growing oppression of ethnic minorities and indigenous populations, aggravate situations of injustice and hopelessness. The ongoing displacement, forced urbanization, repression and increasing incidence of racism of smallholder farmers cannot be tolerated.

7. Democratic control

Smallholder farmers must have direct input into formulating agricultural policies at all levels. The United Nations and related organizations will have to undergo a process of democratization to enable this to become a reality. Everyone has the right to honest, accurate information and open and democratic decision-making. These rights form the basis of good governance, accountability and equal participation in economic, political and social life, free from all forms of discrimination. Rural women, in particular, must be granted direct and active decision-making on food and rural issues.

The acceptance of this framework

[23] in the context of the

Declaration of Human Rights, is extremely important, not only for the small, food-producing people involved, but also for the end consumer in the developed world: the true right to food and the true right to produce food, mean that all people have an unalienable right to safe, nutritious and culturally-appropriate food as well as to food-producing resources, while they have the ability to sustain themselves and their societies in the process.

If the no consensus on a G8-driven global partnership against hunger is the surprise outcome of the High Level Meeting on Food Security held in Madrid in January of this year, it may well be an indication that the food sovereignty movement is conquering terrain. In the final declaration of the farmers' and civil society organizations, they state that:

"We see the proposed Global Partnership as just another move to give the big corporations and their foundations a formal place at the table, despite all the rhetoric about the 'inclusiveness' of this initiative. Furthermore it legitimates the participation of WTO, World Bank and IMF and other neoliberalism-promoting institutions in the solution of the very problems they have caused. This undermines any possibility for civil society or governments from the Global South to play any significant role. We do not need this Global Partnership or any other structure outside the UN system."

[24]

After all, until a few decades ago, it was primarily the small farmers of this world who sustained us all with their hard work in the field.

Footnotes:

[1] "The Cordoba process was started at an international seminar on the right to food at CEHAP [Chair of Studies on Hunger and Poverty], Cordoba October 2007, further pursued at the Right to Food Forum organised by the FAO Right to Food Unit in October 2008 and completed in its present version following a second meeting convened in Cordoba by CEHAP on November 28-29, 2008. It will be subject of further consultations and possible revisions during 2009." Source. [5] Sen, Amartya (1981): "Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlements and Deprivation," Claredon Press, Oxford. [7] Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 US 303 (1980) [9] For a brief history of the seed industry, see here and here. [10] The ETC Group, an international advocacy organization based in Canada, has been monitoring corporate power in the industrial life sciences for the past 30 years, revealed this in a report in November 2008 that can be downloaded here. [11] General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, 1947. A tariff is a tax on goods upon importation. [14] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Report 2005, p.129 vv. [15] UNDP Human Development Report 2005, chapter 4. [17] Raj Patel in "Stuffed and Starved" (2007), London Portobello Books, describes this process in detail. [19] Fourth Special Session of the Committee on Agriculture (2000). [20] Jonas Vanruesel, 2008. "Food as a human right: a struggle for human dignity and food sovereignty" in Omertaa Volume 2008/2. [22] A concise summary of the principles of food sovereignty can be found on the site of the organization for the defense of family farms in the USA.